Glass-Lined reactors are used in number of difficult environments. Some are difficult due to the chemistry of the contents, while others are challenging due to the need to protect the contents from contamination. In either case, one of the more important areas to pay attention to is the shaft seal on the agitator. This is the part that prevents the contents of the reactor from escaping during operation, which could cause harm to the environment, the equipment itself, and any personnel in the vicinity. There are a number of different options for shaft seals and it is important to pick one that matches the requirements of the application.

Seal BasicsThere is a lot of readily-available information on the web about how mechanical seals are designed and how they operate. For starters, here's a tutorial on theIntroduction to Sealing Mixers in the Pharmaceutical and Biotech Industries by Robert A. Smith, Senior Engineer at Flowserve. Additionally, there are a number of articles collected by the Fluid Sealing Association courtesy of Pumps and Systems Magazine on the topic of seals. Wikipedia is also a good source for brushing up on the basics. For glass-lined reactors, it is important to pay attention to the materials that make up the different parts of the seal. Many utilize metal and elastomers that are not compatible with the process environment (which is why you are using glass-lined equipment in the first place!). However, there are several designs available from most of the major seal manufacturers that do have appropriate materials of construction for applications involving glass-lined equipment.

“Wet Seals”Wet seals use a liquid barrier fluid to provide lubrication and contain the contents of the reactor under pressure. This design has been around for a long time and is still used in a lot of applications where customers can tolerate the barrier fluid leaking into the reactor (albeit in very small quantities). Wet seals utilize a seal pot (or what we call a “lubricator”) to act as a reservoir. The lubricator is pressurized and the fluid circulates naturally through the seal. In some cases, a pump is introduced to force the circulation of the sealing fluid. Wet seals are almost always required when operating pressures exceed 150 PSIG or when operating temperatures are in excess of 350°F.

“Dry Seals”Dry seals get their name because the liquid used as a barrier fluid in wet seals is replaced with a gas, normally Nitrogen. By using Nitrogen instead of a liquid barrier fluid, contamination from the fluid leaking across the seal faces is eliminated. Dry seals use seal faces made from special grades of carbons and have been machined to extremely tight tolerances to reduce the amount of wear during operation. Some are even designed to “lift off” and not contact during operation to further reduce the amount of wear, since wear leads to seal failure and can also contaminate the reactor contents. However, it is impossible to eliminate face wear altogether, especially during the starting and stopping of the agitator.

High-Purity Seals

For many Pharmaceutical applications (or others where preventing contamination of the batch contents is critical), the particles being generated due to seal face can be problematic. In these cases, some designs employ a “debris well” that hangs below the seal in the vapor space of the reactor. This debris well is made of a high-alloy material that will withstand the chemical environment inside the vessel, and its purpose is to catch a high percentage of the carbon particles before they fall into the reactor contents. This debris well needs to be cleaned out on a periodic basis between batches.

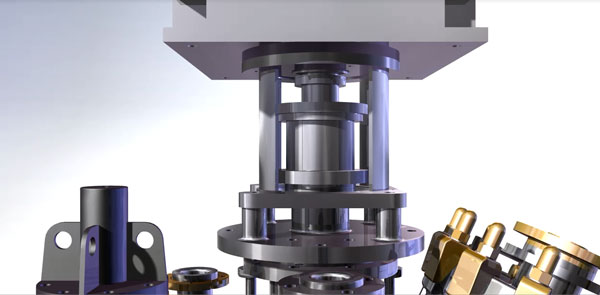

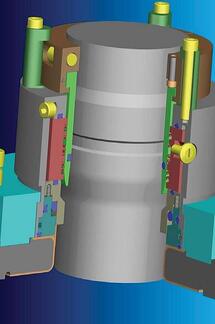

Recently we have partnered with A.W. Chesterton to develop a seal for glass-lined reactors that eliminates both barrier-fluid and seal-face contamination. This seal, which we call our “Optiseal”, utilizes nitrogen to energize a PTFE sealing element inside the seal. There are no carbon surfaces to wear, thereby eliminating the potential for carbon particles making their way into the batch. This seal is also very rugged, since the major components are made from ceramics or fluoropolymers, thereby allowing it to handle runout in excess of 0.250”.

All of the different types of seals have applications where they have proven to be reliable for long periods of time. However, if the process needs are not fully understood or taken into account, specifying the wrong type of seal can lead to premature failure, batch contamination, or safety/environmental issues. Understanding the process conditions, equipment operation, and cleaning requirements are essential in order to select the seal that’s best for your needs.

To see our OptiSeal in action and learn about the other enhancements available for glass-lined reactors, watch our animation “Optimizing the Glass-Lined Reactor” or our Optimizing the Glass-Lined Reactor eBook.

|手机版|蒲公英|ouryao|蒲公英

( 京ICP备14042168号-1 ) 增值电信业务经营许可证编号:京B2-20243455 互联网药品信息服务资格证书编号:(京)-非经营性-2024-0033

|手机版|蒲公英|ouryao|蒲公英

( 京ICP备14042168号-1 ) 增值电信业务经营许可证编号:京B2-20243455 互联网药品信息服务资格证书编号:(京)-非经营性-2024-0033